Is Whole Life Viable for Anyone? New Policies- Rarely; Old Policies- Sometimes Case Study #14

I’m wrapping up a case that illustrates some guidelines applicable to many. This client is smart, financially gifted, well managed, mature, but he made a decision five years ago regarding a whole life policy which he is reconsidering and sought my advice.

The issue of “whole vs. term and invest the difference” is something I cut my teeth on 40 years ago when entering this business as a full-time life insurance agent with Northwestern Mutual, and I became adept at promoting whole life’s virtues.

The debate is done best when refined: the best cash value insurance vs the most competitive term with the difference invested most effectively. This client had a whole life policy that is superlative for two reasons:

- Northwestern provides probably the best whole life value in the marketplace. (That’s why I spent 15 years selling them.)

- The heavy front-end load has been paid on this one, so it’s elite.

Jim is a 56-year-old electrical engineer, with a homemaker wife, grown kids, 1.25 million in 401k/IRA’s, healthy emergency fund, and no debt. He’s healthy and thinks he’ll live to late 80’s (though stats say mid 80’s), but either way is 30 years.

Keeping an old policy, where the onerous initiation fee (commissions) have already been paid, is very different than the question of buying a new one.

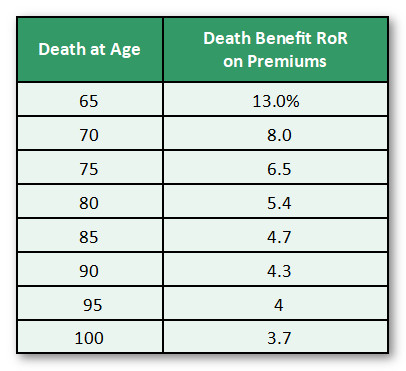

As I typically do, I got an in-force ledger, and NML shows the rate of return on the premiums with respect to the death benefit with insured dying at various ages.

Ruminate on these a bit. Early death yields the greater return (but the odds are low), death at normal life expectancy is mediocre, and at older ages is even lower. Whether the normal life expectancy’s 5% is “good” or “bad” all depends on alternatives. After all it’s likely a 30-year investment for Jim.

This puts before us, on a silver platter, the essence of the decision. “Insurance” is a misnomer for the inevitable, since as my favorite line from Brave Heart goes, “All men die.” For Jim 95% of the premium goes into investment and 5% for insurance. The investment portion goes mainly into bonds and mortgages with inherently lower returns. The mortality aspect costs more than a term policy. Expenses are exorbitant.

What if Jim redirected the NML cash value and premiums into other investments? What would they grow to by normal life expectancy of age 85?

Such a 30-year (long-term) investment lends itself to equities with higher returns, albeit higher volatility too, for three reasons:

- Life insurance is a longer-term investment than even retirement funding.

- The dollar-cost-averaging nature of how premiums are paid in over decades.

- The high expense load of a whole life policy hits your net worth far worse than dollar-cost-averaging into the worst possible equity investing scenario, e.g. starting off at top of market bubbles like Dec. 1999 or fall 2007.

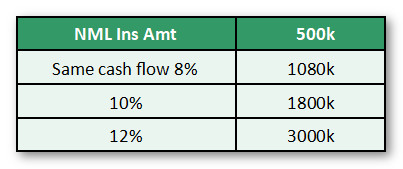

Let’s see what’s at stake. The Northwestern policy would have a death benefit at age 85 of $500k based on the current dividend scale with dividends buying paid up additional insurance.

If its current cash surrender value, along with scheduled premiums were redirected to alternative investments over the same time, it would accrue to these:

Qualifications: I assumed with “Same cash flow” scenarios that Jim bought a comparable amount of term insurance to replicate the NML death benefit in event of an early death, reducing the cash flow into the alternative investment. Jim is self-insured through other assets so won’t buy a term policy, making his investing alternative numbers a tad better than what’s shown here.

In a sense, this is a definitive comparison, bending over backwards to help whole life win, because I’ve cherry picked an elite commission-already-been-paid policy. You can’t go out and buy something this good.

The engine that drives this comparison is equity investing at 8-12%. I have monitored returns from various investment strategies and these are realistic, even the 12% that may seem like a stretch, if greater volatility is acceptable, as it should be when dollar-cost-averaging into an investment over many years.

The difference is invested in Roth IRA’s because it mimics the tax-free nature of life insurance death proceeds. (Roth’s are tax superior overall.) In my early years there was no comparable tax rival and even today NML’s ledger shows total insurance rate of returns assuming a 28% tax bracket, inflating the actual rate of return. This is irrelevant when using the Roth, a nail in the coffin of whole life. The other nails are higher equity returns, lower expenses via no-load mutual funds and ETF’s, and cheaper mortality cost through level term policies, which can be tailored to degree needed, rather than yoked to the investment, as in whole life.

In Jim’s case, since he already maxes his and his wife’s Roth’s each year, he will begin to fund Roth’s for his adult kids. This is vulnerable to being unraveled, so must be done carefully. But it also offers the opportunity to educate your kids about beneficial investing principles, rather than passively paying money to an insurance company for decades, probably worth the risk for the future generation.

Why do consumers miss out on the better opportunity?

- Consumers are responders rather than initiators. The industry has an army of agents promoting cash value insurance, whereas alternative better uses of money has few advocates and depends on consumer initiative.

- It’s easy to miss the dramatic advantage of 8-12% vs 5%. Consumers don’t know how to carefully evaluate; they may not comprehend opportunity cost.

In summary, when I look at least doubling the result for heirs compared to a five-year-old whole life policy with a premier company like NML, I can categorically say whole life policyowners ought to do like Jim and rethink.

So, what’s Jim going to do? Cash out his NML policy and fund Roths? Not so fast. There’s often some salvage value in an old policy. Many advisors make sweeping disparagements leading clients to throw the baby out with the bathwater.

Whole life is a poor long-term investment, but an old NML policy cash value earns an attractive dividend interest rate. It’s cash value of about 50k is about the same as Jim’s emergency fund currently earning 1.2%. If he takes a paid-up policy, then without future premiums, the cash value grows by 3.5% each year (aside from a little extra death benefit). Earnings are tax-free until he recovers the loss he has in the policy. This liberates his current emergency fund for equity funds for those higher long-term returns.

Buying a new whole life policy is rarely a good idea. What to do with an old one is best decided with experienced counsel. Your current need for coverage, your health, knowing the real dividend interest rate on your current policy, taxable gain at surrender, possibly consolidating it with another life policy or annuity to not waste a loss, Roth eligibility, investing strategies… all influence this “rarely” and “sometimes” decision.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!