Defined-benefit Pension Plan Survivorship Election Life Insurance You Choose at Retirement

Defined-benefit pension plans pay a monthly income for life regardless of stock market fluctuations or how long you live. Sweet. However, participants must make a life insurance decision at retirement. It may not look like life insurance, but that’s what it boils down to. They don’t pay a premium as one does with life insurance; instead they take a reduced income. Beneficiaries don’t receive a lump sum at the pensioner’s death as with a policy; rather they receive a continued lifetime income. It’s life insurance in disguise.

The retirement income formula from a defined benefit pension often goes like this: your number of years of service (say 30 years), times a factor (say 2%), times salary at retirement (say $5000/month). This yields $3000/month lifetime income ending at death. Or a reduced pension of perhaps $2500/month for life with a portion to continue to one’s spouse until their death. The proportion continuing can vary (say 100% or 50%) and the higher it is, the lower your pension.

There are at least four aspects of this decision which warrant careful consideration.

- Don’t get tunnel vision. Predeceasing your spouse isn’t the only contingency to address. What if you took the lower income to provide a survivorship benefit but then one of you needed long-term care? Having an extra $500/month would come in handy.

In considering which survivorship benefit, carefully evaluate the needs of your mate and assets to meet those needs apart from a survivorship benefit: the higher of the two Social Security checks, earnings from an IRA, spouse’s income capacity, and other life insurance. You may be self-insured and the cheapest form of insurance is self-insurance. While few married retirees take no survivorship benefit, most should take less than 100% to the survivor, since it takes less for one person to live than two: one less person eating, clothing, one less car, etc.

- Remember the defined benefit pension survivorship benefit is “life insurance” not subject to insurability: no insurance exam, bloodwork, questions about health history, driving record etc. For insurance companies this means adverse selection, i.e. those who elect it are often in poorer health and a higher risk. This means that for a non-smoker in good health, with good parental longevity, it’s probably a poor value.

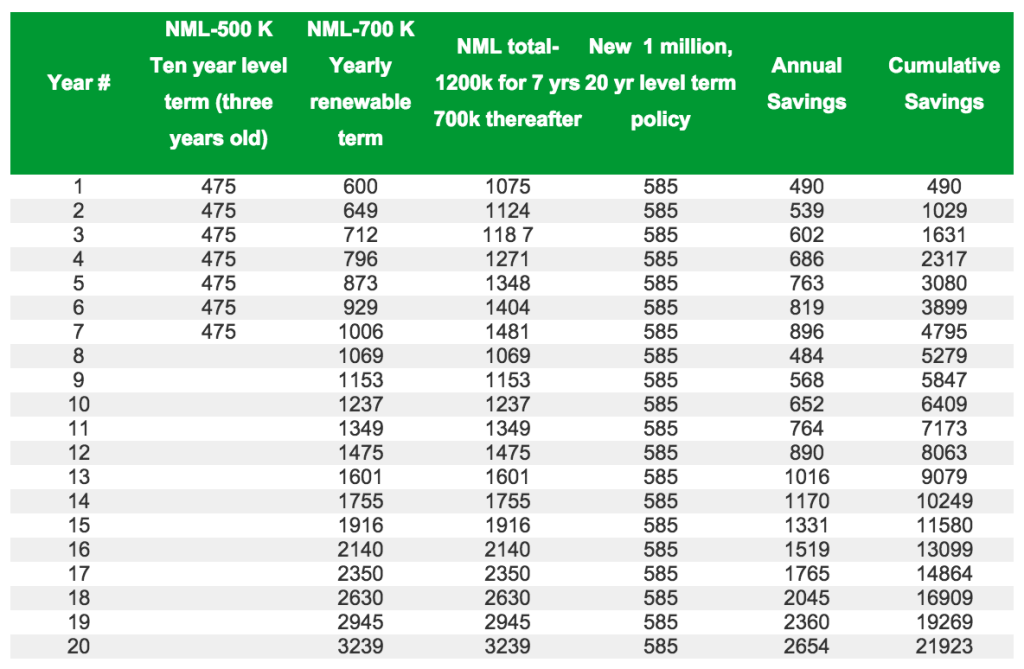

- You could take the extra income from not having a survivorship benefit and buy your own policy. Agents see this as a sales opportunity, but be careful. Just because you get $500/month extra by forgoing a survivorship benefit doesn’t mean it’s best to put that amount in a policy.

Suppose when you reach retirement things still aren’t quite where you want them. You might get a 10-year level term policy, buying a bit more time to finish the mortgage, get closer to Social Security age, etc. However just because you could do it (and it may be the better value), doesn’t mean you should do it. There still may be better uses of that money. The likelihood of a healthy 65-year-old dying before the end of a 10-year level term policy is still very small.

Your mate’s sentiments are key. Start by looking at what their income would be at your death without survivorship benefits. Then compare it with the lifestyle you want to ensure and their comfort level.

- Since the future is unknowable, an advisor can’t definitively tell you what to do. There are risks each way. You could forgo the survivorship benefit and die early, or you could elect a survivorship benefit with its lower income for decades, and then your spouse predeceases you.

In summary, look at your assets and liabilities and carefully evaluate your life expectancy. Pray for wisdom from Him who, according to Psalm 139:16, knows the day we will die. Keep in mind survivorship benefits may not be a good value for the healthiest. Finally, it’s usually best to make the high probability decision, if the lower probability scenario is addressed other ways.

This may be the most important life insurance decision you ever make. It will govern your and your spouse’s income for the rest of your lives, and because it involves two lives, its impact often lasts three decades.